Do not ask who I am and do not ask me to remain the same;

leave it to our bureaucrats and our police to see that our papers are in order.

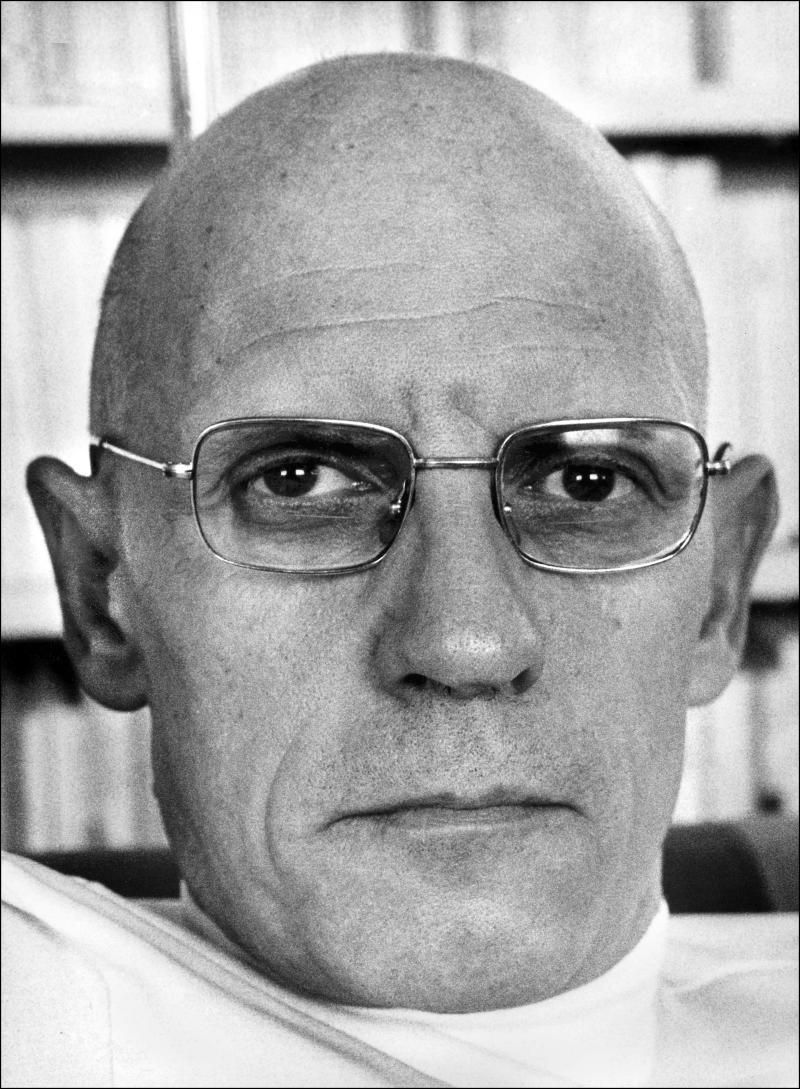

Michel Foucault

Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison

(Surveillance et punir: la naissance de la prison)

This is an essay about the changes in human culture inflicted by technological changes that alter the public and private bureaucratic cultures in which we all operate. In other words, the very way the mind works has changed as technology has increased and the capacity for collective social knowledge has grown. This essay seeks to capture the key insights of the now much-forgotten French philosopher-sociologist Michel Foucault, and his once popular concept of pouvoir-savoir ("power / knowledge"): the notion that power and knowledge are really two sides of the same coin in understanding the operation of society. His central thesis was that as we learn ever more as society as a whole - in other words, as science and then later the consequent technology we develop from our increases in scientific knowledge, increases - our collective social minds become ever more loaded with information and conventions and that this restricts our channels of thinking and renders our thought and behaviour ever more predictable and rules-governed.

In other words, the distinctively unidirectional quality of scientific learning (we cannot unlearn scientific knowledge, and hence we cannot deconstruct the effects of the technology it gives rise to) causes human beings to turn ever more into machines, whose lives are operated by bureaucratic rules-governed procedures many of which are external and many of which are internalised into the way each individual thinks and acts. In other words, individual people and society as a whole become ever more harmonised in the way they act; they all start to act more like one-another and they all start to become more predictable. And then, in a typically French philosophical twist, Foucault concludes that this means that we are all less free as a result. In other words, science and technology do not liberate us from our chains of social slavery; instead they reinforce those chains by turning us all into mental machines. Science eliminates both the mind-body problem and the freedom of the will problem at a stroke, by turning minds into machines and denying us our liberty.

Michael Foucault was a very unusual man, with some very unusual ways of expressing his ideas (and they read even more unusually in their original language of French). Nevertheless here is another famous quotation of his, that illustrates his curious assimilation of prisons (places that deny people liberty) and schools (places that in his view do the same thing because they teach people things and that turns them into automata).

Is it surprising that prisons resemble factories, schools, barracks,

hospitals, which all represent prisons?

Michel Foucault

Discipline & Punish: the Birth of the Prison

(Naissance et punir: la naissance de la prison)

In other words, social institutions are like prisons because they invest into individual and social psychology sets of rules, norms and procedures purportedly based upon technical knowledge and impartial bureaucracy-based reasoning and this process of "normalisation" of human behaviour in fact has the result of homogenising human behaviour into a singularity, just like behaviour in a prison. And, like in prison, this deprives us of liberty. Social harmonisation and impartial bureaucratisation caused by the growth of knowledge creates within each of us a prison of the mind.

Michel Foucault, one of the most unusual characters in the history of political and social thought, but replete with long-forgotten ideas with curious resonance in the contemporary era. Those interested in the influence of technology on society, and on issues such as corporate and electronic profiling, may find his work of particular value.

---

We now live in an era of prolific electronic profiling. What we mean by this is that both private organisations and governments collect massive quantities of information about us by monitoring our electronic activities. The sorts of electronic activities that are monitored include the contents of emails; the sorts of people emails are sent to; the contents of other electronic messages (including instant messaging systems); the people appearing in our address books on our mobile telephone devices; the information we post on social media networks; the information other people with whom we are connected post on social media networks; the Russians are believed to use facial recognition technology to collect information about persons; the sorts of things we buy on websites; information about location, purchases, our personal lifestyle choices and commercial activities collected by mobile telephone Apps; and a great deal more.

This information may be used to create profiles of our personalities; our social class; the sorts of people we are likely to become friends or lovers with; the sorts of work we are attracted towards and the sorts of jobs we might be interested in applying for; the sorts of vacation we might wish to go on; the sorts of car we might want to buy; and so on and so forth. In short, the international community of owners of electronic information about persons is so gargantuan that there are now electronic profiles out there for all of us, and in most cases more than one such profile. Our personal data is then sold by each of the private companies involved to one another for miscellaneous cross-marketing purposes, creating ever more exponentially detailed profiles of each of us as individuals and of those we know.

Profiling is not new. Vance Packard described it in the context of the rise of commercial advertising in his 1957 pioneering work The Hidden Persuaders. Nonetheless whereas marketing companies have always been collecting information about their potential customers, as have political parties (one of the purposes of political parties going door to door during election campaigns is to collect information upon the political leanings of each of their individual constituents) and indeed government agencies (a little known secret of Britain's National Health Service is that any patient with a lawyer in the family has their file discreetly so marked so as to receive superior service to foreclose medical negligence litigation risk), the growth of information technology and electronic databases has made the possibilities for collecting profiling information on individuals all the more remarkable and, essentially, all the more cheap and easy.

Foucault did not anticipate these things when he was writing, for the most part in the 1970's and early 1980's, because the information technology boom had not yet taken off. Instead he was focused upon prisons because he saw the development from medieval technologies of punishment, in which witches were burned, thieves would have their hands cut off, and traitors would be beheaded, to the efficiencies of Bentham's Panopticon in which a maximum number of prisoners could be supervised by a minimum number of guards through placing a single guard in the centre of a cylindrical building with open cells facing into the central space of the prison so that the prison guard could observe all the prisoners at once, as an increase not in humanitarianism but in the capacity to use resources to control people efficiently. Hence Foucault's focus was to demonstrate that what we imagined to be the enlightened forward direction of history towards ever-increasing humanitarianism really to be masquerading as a system of control over people and the way they thought, this increased repression being the consequence of ever-advancing technology. And advancing technology is a ratchet that cannot be reversed. Hence, in Foucault's mind, society is becoming ever more oppressive and unfree, and continuing his prison analogy, he named modern living "the carceral society". This horribly evocative phrase suggested that we are all living in a giant prison, in which our every decision is anticipated by efficient technological forces that manipulate both what we can physically do (this can be a matter as trivial as the alarm clock) or how we think and hence how we are going to act. The more an organisation knows about a person, the more they can fine tune their interactions with that person to cause them to act in a desired way. Foucault thought that this trend consists in the abnegation of freedom,

Foucault did not anticipate these things when he was writing, for the most part in the 1970's and early 1980's, because the information technology boom had not yet taken off. Instead he was focused upon prisons because he saw the development from medieval technologies of punishment, in which witches were burned, thieves would have their hands cut off, and traitors would be beheaded, to the efficiencies of Bentham's Panopticon in which a maximum number of prisoners could be supervised by a minimum number of guards through placing a single guard in the centre of a cylindrical building with open cells facing into the central space of the prison so that the prison guard could observe all the prisoners at once, as an increase not in humanitarianism but in the capacity to use resources to control people efficiently. Hence Foucault's focus was to demonstrate that what we imagined to be the enlightened forward direction of history towards ever-increasing humanitarianism really to be masquerading as a system of control over people and the way they thought, this increased repression being the consequence of ever-advancing technology. And advancing technology is a ratchet that cannot be reversed. Hence, in Foucault's mind, society is becoming ever more oppressive and unfree.

Continuing his prison analogy, he named modern living "the carceral society". This horribly evocative phrase suggested that we are all living in a giant prison, in which our every decision is anticipated by efficient technological forces that manipulate both what we can physically do (this can be a matter as trivial as the alarm clock) or how we think and hence how we are going to act. The more an organisation knows about a person, the more they can fine tune their interactions with that person to cause them to act in a desired way. Foucault thought that this trend consists in the abnegation of freedom, because he saw people as having fewer personal choices if they are forced into making the decisions they do or are manipulated into making them by reason of the external influences consciously being brought to bear against them due to the collection of external knowledge about how they were likely to react. Free will, as philosophers have traditionally posited, stands in contrast to determinism; and being manipulated into making decisions by playing upon the internal desires of a human being is the very essence of liberty-quenching determinism.

This gives rise to a fundamental metaphysical question for the modern IT-dominated society: is all this information technology, and the electronic devices that we carry around in our pockets daily and that Foucault never had access to (he died in 1986), really a good thing for us? What are the tangible material and other personal utility benefits of the growth in technology compared to how we used to live before, and how should they be weighted against the loss of liberty that the exercise in profiling electronic communications has caused to grow so colossally? There are no easy answers to these questions, but Foucault's insights suggest that these are at the very least questions that should be explored if we are to make an assessment of whether as a world we are becoming a better place to live in. Electronic technology is now so all-pervasive in the lives of virtually everyone on the planet, from the residents of the wealthiest metropolises to the poorest people living in rural conditions in some of the poorest corners of the earth, that the net beneficial effect of all this technology is something that surely needs to be evaluated. Is it a good thing that we all now walk around with electronic devices in our pockets that are engaged in persistent exercises in profiling us ever more closely?

We give an example. There is a mobile telephone application, commonly available in Russia, that permits its user to do the following. Let us imagine that one sees on the Moscow metro an attractive person that one would like to maintain contact with. They could be a complete stranger. In times past, the appropriate procedure would have been to approach this person and ask for their contact details with their consent. But it turns out that this is no longer necessary. Using this Russian application, which shall remain nameless in this article because it involves so egregious a violation of what we consider to be elementary civil liberties, all one need do is to point one's mobile telephone at the pretty girl sitting opposite you on the Moscow metro and her full personal details will come up on your mobile device, including her full name, her address, her telephone number, her social media details, her email address(es), her car type and registration number, and a series of other personal details about her and her personality insofar as the application database has this information. This may be a horrifying extreme; but it represents a truly alarming development and it would be fanciful to imagine that if this technology already exists in Russia then at some point it will not also spread to other jurisdictions. There is undoubtedly something very wrong with this, and the propagation of such technology presents a major regulatory challenge for those of a liberal political disposition in the western world. It also raises a range of issues about the relationship between the government and the individual, because if a private software application has this capacity than you may rest assured that the governmental authorities of the country in question have that capacity as well.

Undoubtedly one of the vices that has driven this Russian software is the Russian government's propensity to collect as much personal information about its population as it possibly can; and this has been a recurrent feature of Russian security and intelligence service activities throughout the history of the Russian Federation, the Soviet Union and even during historical periods before that. This vice is combined with a second, namely unclear demarcations between the public and private sector that allow a presumptively private sector Russian company to access Russian government databases seemingly without restriction. The concern of course is that the whole project is run as a pilot programme by the FSB or something of this ilk.

There is an argument for discarding our mobile telephones, which are now the principal sources of collecting profiling information. There is a physical world out where in which we are not (or no longer) aggressively profiled, and we might spend more time focusing upon that real world, and all the real things going on in it, than in being influenced by the torrent of information flowing in both directions into and out of our mobile telephones. We might wean ourselves off our addictions to the virtual world, and replace them with what we had before, namely our joyous experiences of the real world that amidst all this deluge of mobile technology are being lost somehow in the mists of miscomprehension, disinformation, manipulation and abuse. We need to learn how to become free again.

Foucault's thinking became gradually neglected after his death, particularly outside the French-speaking world. But arguably it has acquired a new urgency in the world of artificial intelligence, electronic profiling, computational essay writers that are indistinguishable from humans and a barrage of other electronic innovations that compromise the capacity of the individual human being to think for him or herself. The origins of this exercise in emasculating human autonomy was the growth of scientific knowledge and the concomitant development of technology. Or, as Foucault put it:

The 'Enlightenment', which discovered the liberties, also invented the disciplines.

There is much to be said for rereading Foucault today and reflecting upon his wisdoms in this increasingly complex, bewildering and frightening electronic world.

---

Post scriptum

The American actor William Shatner, in the earth-shatteringly hilarious movie Airplane II that went to movie theatres in 1982, delivered a series of deadpan lines as the commander of a fictitious lunar base about how complicated all the computers and equipment on board his base were that sum up modern frustration with the complexity of technology. The scene was well before its time; he captured over 40 years ago the contemporary frustrations we all feel today with being unable to understand the technology that invades our lives at every opportunity.

It is a shame that so little modern cinematography captures the genius and wisdom of this old classic, and that brilliant actors like Shatner are now in such short supply.

Comments